A dispute between Papua New Guinea and Canada's Nautilus Minerals threatens to sink plans to mine gold and other metals for the first time from the ocean floor. It could also work against Papua New Guinea's efforts to restore faith in its vast resources potential and entice more foreign companies to follow the likes of Exxon Mobil, Newcrest Mining and Barrick Gold and invest billions of dollars in resource projects.

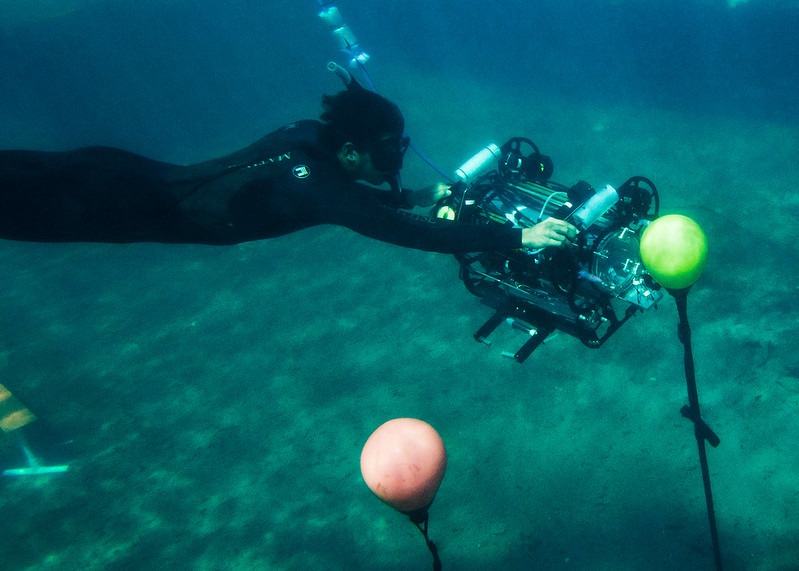

A dispute between Papua New Guinea and Canada's Nautilus Minerals threatens to sink plans to mine gold and other metals for the first time from the ocean floor. It could also work against Papua New Guinea's efforts to restore faith in its vast resources potential and entice more foreign companies to follow the likes of Exxon Mobil, Newcrest Mining and Barrick Gold and invest billions of dollars in resource projects.In the ground-breaking venture, Nautilus hopes to send robots a mile under water to mine the sea floor near hydrothermal vents that deposit copper, gold and other minerals.

Hungry for foreign investment, Papua New Guinea, a nation of 7 million spread, agreed in 2011 to pay 30% of the costs to build the Solwara 1 project in the Bismarck Sea, which Nautilus said amounts to $80m so far.

But in June, the government's investment arm, Petromin, said it was terminating the agreement. Without the funds, Nautilus says it cannot afford to proceed and the matter is now in arbitration in Australia under the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (Unictral).

Nautilus' shares have tumbled 60% since it announced in mid-November that it was laying off 60 workers and halting work on the project to save cash. Chief executive Michael Johnston said another round of job losses would follow on Friday unless a resolution could be reached.

"We don't know where we stand at the moment," said Johnston. "We're optimistic because we have to be, but we just don't know what Petromin is thinking."

Papua New Guinea has been described as an island of gold floating in a sea of oil, surrounded by gas, but consistently punches below its weight on the global resources stage.

The impoverished country has a long legacy of mining projects derailed by environmental disasters, landowner uprisings and corruption. Mining from vessels is seen as a way of avoiding some of the landowner disputes that have plagued other projects. Still, the project has been criticised for failing to adequately assess environmental risks.

"No one knows what the impacts of this form of mining will be," said Wences Magun, national co-ordinator for Mas Kagin Tapani, a Papua New Guinea environmental group.

"Communities want to know what concrete steps the prime minister will now take to ensure we are not being used us as guinea pigs in a sea bed mining experiment."

Johnston insists international environmental safeguards were applied to the project before a permit was granted in 2009, and that it poses no major threats since all the material mined is used, alleviating harmful waste generation.

"The deposits are mainly on the surface of the sea floor," he said. "No mountains need to be removed, no trees need to be cleared."

Petromin was set up five years ago to buy into foreign projects and safeguard revenues earmarked to help local communities. The fund has invested in 17 projects, including a $19bn liquefied natural gas project under construction by Exxon Mobil. It is also working with Shell to identify untapped oil and gas reserves.

It is allowed to take up to 30% of mining and 22% of oil and gas projects, which it must then help fund. Petromin has said little publicly about the Nautilus dispute, other than that the Canadian firm had not met certain undisclosed obligations under its agreement, which entitled it to terminate the pact.

Petromin did not respond to requests for clarification over its reasons for terminating the agreement and Nautilus said it had no more details surrounding the decision.

Source: The Guardian

Photo courtesy of US Navy Imagery via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)